"It sounded like thunder," he recalled.

I always enjoyed listening to his memories of the war -- the small, human experiences that stayed with him.

One of my favorite stories was about coming into a small, burned-out village somewhere in France. His company had come into town after a long march.

"Every building had been damaged or destroyed," he said.

He told me that there was this one little shop still untouched, the big picture window still intact.

"I was so tired. And I sat down outside the shop and leaned against the window and it shattered. The shop owner came running outside, crying and cursing in French. Every time I think about it, I feel bad," he said. "I felt so bad for him."

Another time, he remembered a German woman calling to him, shouting, "Schießen die katze!"

"Nazi? Where?" he asked.

Then he noticed she was pointing at two cats mating. She wanted him to shoot the cat that was violating her female katze.

"Nein," he said. "I couldn't shoot a cat."

He loved animals. His grandmother wrote to him while he was in bootcamp that his little dog, Tippy, had been hit by a car.

"She shouldn't have told me," he said. "I went behind the barracks and cried and cried. I couldn't eat for two weeks. I lost weight."

When I looked up his army records not long ago, it said he weighed all of a hundred pounds when he shipped for Europe on the Queen Mary.

"The ship zigzagged all the way across the ocean," he said, "…so it would be harder for submarines to fire on us. It took about 15 minutes for the ship to list to one side, then 15 minutes for it to list to the other. I've never been so sick in my life. I took my pack and climbed into a lifeboat to sleep."

My dad loved guns. And all he wanted to do was collect as many German guns as he could while he was there. He didn't smoke, so he often traded cigarettes for weapons. Once when I was home visiting from California, he told me a story about bringing some guns home. He was somewhere in Germany in a bombed-out castle. He was trying to find something to wrap up some guns he'd found lying on the ground.

"I saw these two paintings," he said. "So I took my bayonet and cut them out of the frames."

Then he brought them out. I couldn't believe my eyes. Here were two large paintings -- one of Himmler and one of Goering.

|

| Liter-size bottle for perspective |

|

| Hermann Goering |

|

| Heinrich Himmler |

"They'd leave the German bodies for the morale of our troops," he said, and to demoralize the German troops."

He remembered being encamped in a little house one freezing German night.

"There was the body of a young soldier in a room in back," he recalled. He couldn't have been more than 17 or 18." My father was only 18 at the time.

"We came back through about three weeks later. The body was still there. It was cold, so it hadn't really started to decompose. I just remember being struck that he'd just turned green, nothing else. You know, it didn't bother me at the time. I guess youth is rather callous. But I still see him now, and it bothers me a lot. He was someone's child. How could I have not been bothered then but so bothered now? I see him a lot now. And it bothers me."

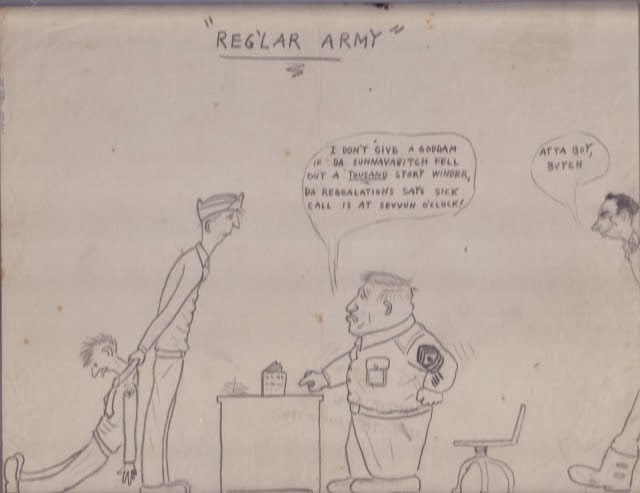

My father was a talented artist, though he never really used his talent for much. But he had a great time making fun of his commander and other officers during training. He'd draw cartoons of them and pin them on the bulletin board at night when everyone was asleep. It infuriated the officers. Everyone else thought they were hilarious.

They never did find out who the rogue artist was, but he brought those drawings home, and I think he might've missed his calling.

He was just a child, himself, in World War II. After everything was over, he was assigned to watch some German prisoners. He got in trouble once for his trusting, naiveté when he asked a German prisoner to hold his gun for him while he tied his shoe. :) The prisoner held it for him and returned it.

He remembered the German officers who were prisoners, and always saluted them. I think he felt bad for them.

"They all carried those little weiner dogs with them," he said. Daddy liked anyone who liked animals.

He was just a child, himself, in World War II. After everything was over, he was assigned to watch some German prisoners. He got in trouble once for his trusting, naiveté when he asked a German prisoner to hold his gun for him while he tied his shoe. :) The prisoner held it for him and returned it.

He remembered the German officers who were prisoners, and always saluted them. I think he felt bad for them.

"They all carried those little weiner dogs with them," he said. Daddy liked anyone who liked animals.

I arrived to read your post on Prospect Hill, then stuck around. Great stuff. I'm old enough to remember a tour of Melrose conducted by Ethel Moore Kelly herself (of course I was practically a child) and have been mildly stuck on Natchez since. Keep writing!

ReplyDelete